Halliburton's six-chapter treatment of his Devil's Island interlude in his third book, New Worlds to Conquer, was an example of how he could quickly alternate between light-hearted gambits such as his tours with Nino the monkey as an itinerant organ grinder and starkly somber subjects such as his exposures of the infamous French penal colony. My book, A Shooting Star Meets the Well of Death, Why and How Richard Halliburton Conquered the World, relates how by ruse he gained access to that hell hole, obtained information from prisoners, and was shaken by the results of the wretched conditions he exposed.

His treatment of the sprawling prison is worth closer examination, both for his guile in finding a way to place himself there at all and for the effect it had on those French officials who allowed him free access.

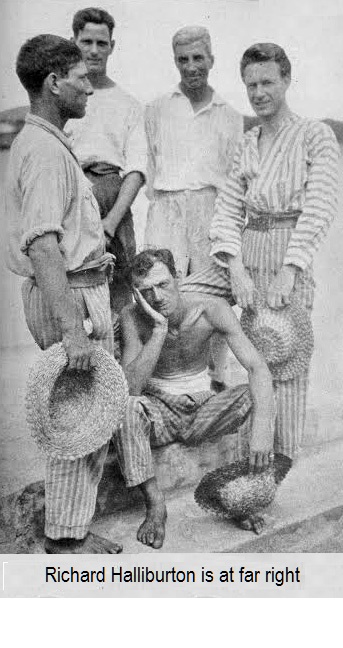

He arrived at Cayenne, the capital of French Guyana, on the first plane ever to land there, a flying boat making a fueling stop on a 1929 inaugural flight from New York to Buenos Aires. This was one year before air mail would begin to be flown from Miami to South America. Knowing the French were always wary of prying eyes toward their harshly administered penal colony and that they would never have granted a writer the chance to visit if asked, he masqueraded as a temporarily left-behind member of the plane’s crew. His guise as an aviator, an adventurous rarity in those days, automatically conferred on him celebrity status. The ruse worked well. He was feted by the Commandant himself, invited to stay as a house guest, and given carte blanche to wander wherever among the islands as he desired. Wander he did for a number of weeks, poking into the squalid corners of the several islands of the penal archipelago and surreptitiously recording horrific tales of mistreatment as endured by prisoners. By bribing the guards, he was able to obtain a convict's suit and to spend nights somewhat uncomfortably, if not dangerously, among the wretched prisoners. He saw, smelled and heard their abject misery firsthand. He also spent a week as a doctor's aide in the dispensary, binding wounds, performing menial tasks and recording more horror stories.

That the six Devil’s Island chapters he wrote were starkly somber and filled with sordid tales told by the hapless unfortunates he encountered was hardly a surprise. For years there had been rumors and reports about utter privation and cruelty in that penal colony. He chronicled what he saw and heard objectively and vividly. The results were serialized in Ladies Home Journal magazine and later in his book New Worlds to Conquer. Although these terrible conditions had been known to exist for years, the glaring publicity generated by Halliburton's writings brought about the sacking of the Commandant and hasty changes.

In an October letter, he wrote, "I want to do another Devil's Island story, using the manuscript and letters I've received. A flock of them came yesterday, some informing me that the kindly old commandant of the islands had been court-martialed because of my visit. He'll probably be shot when my book appears! I'm distressed. The letters from his sister and daughter are pathetic." But he was also comforted by letters of gratitude from relatives of prisoners and prisoners themselves praising the changes his expose had produced on their behalf. Better food became available because graft was reduced and better living conditions brought on by the glare of publicity at least ameliorated the convicts’ miserable existence. He never got around to writing that second story but there was no doubt that his first efforts had a profound impact and led to significant, more humane conditions for the unfortunates imprisoned there.

William R. Taylor www.rhalliburtonstar.com.

His treatment of the sprawling prison is worth closer examination, both for his guile in finding a way to place himself there at all and for the effect it had on those French officials who allowed him free access.

He arrived at Cayenne, the capital of French Guyana, on the first plane ever to land there, a flying boat making a fueling stop on a 1929 inaugural flight from New York to Buenos Aires. This was one year before air mail would begin to be flown from Miami to South America. Knowing the French were always wary of prying eyes toward their harshly administered penal colony and that they would never have granted a writer the chance to visit if asked, he masqueraded as a temporarily left-behind member of the plane’s crew. His guise as an aviator, an adventurous rarity in those days, automatically conferred on him celebrity status. The ruse worked well. He was feted by the Commandant himself, invited to stay as a house guest, and given carte blanche to wander wherever among the islands as he desired. Wander he did for a number of weeks, poking into the squalid corners of the several islands of the penal archipelago and surreptitiously recording horrific tales of mistreatment as endured by prisoners. By bribing the guards, he was able to obtain a convict's suit and to spend nights somewhat uncomfortably, if not dangerously, among the wretched prisoners. He saw, smelled and heard their abject misery firsthand. He also spent a week as a doctor's aide in the dispensary, binding wounds, performing menial tasks and recording more horror stories.

That the six Devil’s Island chapters he wrote were starkly somber and filled with sordid tales told by the hapless unfortunates he encountered was hardly a surprise. For years there had been rumors and reports about utter privation and cruelty in that penal colony. He chronicled what he saw and heard objectively and vividly. The results were serialized in Ladies Home Journal magazine and later in his book New Worlds to Conquer. Although these terrible conditions had been known to exist for years, the glaring publicity generated by Halliburton's writings brought about the sacking of the Commandant and hasty changes.

In an October letter, he wrote, "I want to do another Devil's Island story, using the manuscript and letters I've received. A flock of them came yesterday, some informing me that the kindly old commandant of the islands had been court-martialed because of my visit. He'll probably be shot when my book appears! I'm distressed. The letters from his sister and daughter are pathetic." But he was also comforted by letters of gratitude from relatives of prisoners and prisoners themselves praising the changes his expose had produced on their behalf. Better food became available because graft was reduced and better living conditions brought on by the glare of publicity at least ameliorated the convicts’ miserable existence. He never got around to writing that second story but there was no doubt that his first efforts had a profound impact and led to significant, more humane conditions for the unfortunates imprisoned there.

William R. Taylor www.rhalliburtonstar.com.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed